I’m going to state that the idea of being crushed beneath a building is fundamentally different for New Yorkers than for most USians. People’s minds go to different places based on what they fear. In Florida, I feared tornadoes and hurricanes in the way that Californians fear earthquakes and Hawaiians fear tsunamis. Now I live in New York (and work in a historic building no less) and I fear building collapses in that same way—a dull throb behind all of my conscious thought, occasionally bubbling up into a nightmare.

It’s this aspect of New York that has marked the Marvel Cinematic Universe, and set it apart from the DCU. Marvel is New York. As was said over and over again at the Defenders SDCC 2017 panel, New York is another character in the MCU. As was made clear by Spider-Man: Homecoming, changes to the city itself reverberate through the lives of its characters. In a way that the DCU, with its fictional cities, can never match, New York’s (real and fictional) buildings are the skeleton of the MCU. And that skeleton has been permanently marked by 9/11/01, and the ongoing fight against terrorism in the world. I would argue that it’s this aspect that gives the MCU films a dimension of emotional resonance that transcends their status as popcorn movies.

This post contains spoilers for the entire MCU, the Netflix/Marvel productions, the Spider-Man Trilogy, the Amazing Spider-Man Duology, and The first two X-Men films.

Marvel Before the Cinematic Universe

To talk about this topic, I’ll need to hop back a few years, and start before the MCU took over every aspect of pop culture. When Bryan Singer made the first X-Men movie in 2000, he ushered in the new age of superhero movie. He was working with a team of heroes who were based in upstate New York, but whose backgrounds, like a lot of New Yorkers, are cosmopolitan. The X-Men films feature Brits, Jewish Holocaust Center Concentration Camp survivors, Canadians, Russians, Cajuns, German circus workers. They all come together at the school in Westchester. They go into the city fairly often, and when they face-off with Magneto at the end of the first movie it’s at the Statue of Liberty, because Singer wanted to fashion an iconic terrorist event.

Then reality gave New York a better one.

Sam Raimi’s first two Spider-Man movies (2002 and 2004) took Marvel’s connection to New York and ran with it. After he had to photoshop the World Trade Center towers out of the first film, Raimi added a scene in which a bunch of New Yorkers pelt Green Goblin with bits of asphalt and yell: “You mess with one of us, you mess with all of us!” Spider-Man 2 doubled down with a train full of people protecting Peter after a fight with Doc Ock (the train is elevated, which is dumb, but it’s still a great scene), and then the culmination of the film is a potentially city-flattening explosion.

Both of the Webb/Garfield Spider-Man films feature scenes of ordinary New Yorkers helping the hero:

Emmet Asher-Perrin talks about it in her piece “Spider-Man: Homecoming is the Clearest Vision of Spider-Man’s Most Important Message”—Spider-Man’s essential New Yorkness is part of what makes him such a great hero. No matter where you live, the specificity of his life and struggles in the city become universal, especially to the nerdier among us, so seeing the city embrace him when he needs them is more uplifting than all of the generic statements of Superman giving people hope.

The Marvel Cinematic Universe Confronts Terrorism

But it’s in the MCU that we get the clearest response to the way terrorism has impacted New York. You can read the MCU as an allegory of the US response to terrorism, and its shifting role in the world. Tony Stark is the American warmonger, who saw the light and now wants everyone to stop being mad at him, even though his weapons and tech are still causing misery to people he’ll never know. Cap is the best of America, for better and worse, the deeply moral, well-meaning golden retriever, bouncing around the world trying so goddamn hard to help, and desperately trying to resolve his love/hate relationship with his old buddy Russia, er, I mean, Bucky. Widow’s the espionage community who always has to stay one step ahead, Clint is the military grunt just trying to get through the mission, Banner’s the science community with his own complicated relationship to government and military. That’s all fine. But it’s in their particular obsession with a couple of images that the larger theme comes out.

Did 9/11/01 happen in the MCU? It seems easiest to assume so. The World Trade Center Towers are absent from the MCU skyline, which does feature Stark/Avengers Tower in the films and in the motion posters released for each Netflix series. (No Baxter Building, though.) When we meet Tony Stark in 2008, he’s selling weapons to the U.S. military in Afghanistan, so it’s safe to assume that the US of the MCU is engaged in the same war that our world’s US was. Later, in an outtake from Iron Man 3, a Secret Service agent references Rhodey’s time in “Gulf War I,” so it’s also safe to assume that the earlier war with Iraq happened in the early 1990s, and that Rhodey fought in it when he was in his early 20s. So the situation in the Middle East is essentially the same as it is in our universe.

Iron Man is the one that gives us the closest one-to-one comparisons with the world’s current worst terrorists. It’s also worth noting that of all the Avengers, Tony is probably the least New York of all of them. He’s aggressively Californian, from the house in Malibu to the increasing obsession with health food. (He’s totally the Dawn of the group, is what I’m saying. Cap is the Kristy, Banner’s the Mary Anne, Natasha’s the Claudia, Hawkeye’s the Logan, Falcon’s the Stacey, Scarlet Witch and Peter Parker are Mallory and Jesse.) Tony Stark has an intimate relationship to terrorism in the Middle East. His trilogy pits him against Middle Eastern terrorists, a throwback Cold War terrorist with a personal grudge against Tony, and two rival arms dealers, plus a faux bin Laden character who makes fearmongering videos, and eventually snuff films, that line up precisely with things the Taliban and ISIS have posted online.

In Iron Man, Tony is captured by terrorists in Afghanistan, and only builds his Iron Man suit (in a CAVE, from a box of SCRAPS) because he’s being forced to build a missile. The group broadcasts a video of demands, holding a gun to Tony’s head and forcing him to stare, terrified, into the camera. In Iron Man 2, the terrorist is Ivan Vanko, a Russian who attacks the Stark Expo, a celebration of technology and futurism. In Iron Man 3, the terrorist is the Mandarin, who makes horrifying Taliban-esque videos, plans bombings, and shoots a hostage live on camera.

Now, the interesting thing is that none of these are quite accurate. The first group, while based in Afghanistan, is a multi-ethnic coalition, with members from India, Afghanistan, the Arabian sub-continent, and Hungary—but they aren’t calling the shots. We soon learn that they’re just muscle employed by Tony’s business partner, Obadiah Stane, who wants Tony out of the way. Stane kills them once he’s done with them. The next Big Bad, Vanko, only attacks Tony because of a personal vendetta against the Stark family. Here again, though, the villain is a pawn used by Tony’s main competitor in the fine art of war-profiteering, Justin Hammer. And finally the trilogy’s conclusion takes this theme to its natural endpoint by setting up the Mandarin, who isn’t even a terrorist–he’s just a drug-addled, lascivious actor named Trevor. He’s a fake terrorist funded by yet another man with a personal grudge against Tony, inventor Aldrich Killian.

In each instance, the real Big Bad, behind all the showy terrorist trappings, is a white man who wants to win at capitalism—or more specifically, wants to beat Tony Stark at capitalism.

Tony, meanwhile, receives an abrupt lesson in mortality from his chestful of shrapnel. I find it easiest to read Tony’s career in warmongering as a response to the terrorism that happened in our timeline—he grew up profiting from it, and developing his own StarkTech with money made from wars he never had to fight in. Once he realizes what life is like for those in war he backs away as fast as he can, and begins converting his work to peaceful causes. And because the MCU started with Tony, its themes are permanently interwoven with the conversation about terrorism.

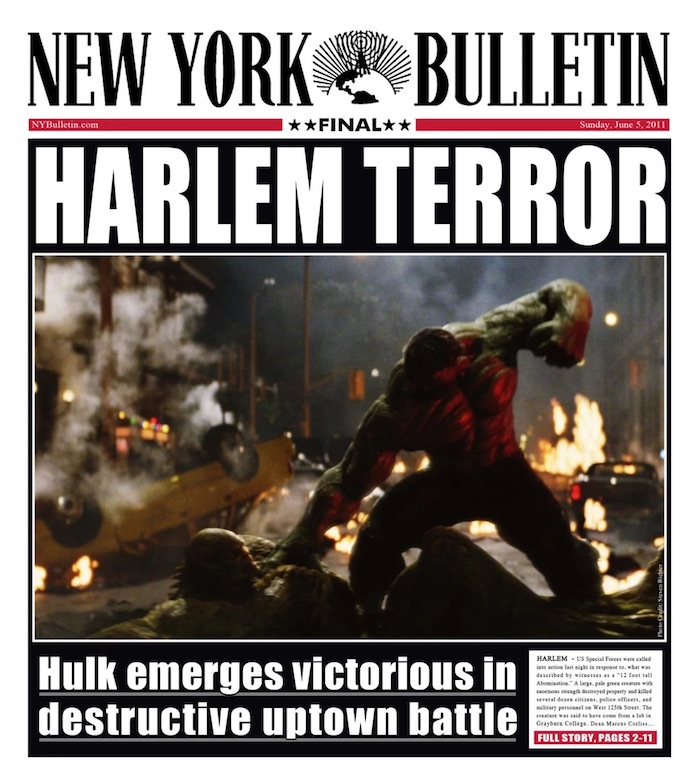

The Battles of New York

There are two battles of New York, but only one is really discussed. The first is in 2008’s The Incredible Hulk, when two giant rage-monsters, science experiments gone wrong, rampaged through Upper Manhattan and, well, “broke…Harlem” as Bruce Banner later sheepishly admits. This incident, the centerpiece of one of the MCU’s least successful films, is played for laughs in The Avengers, but we later learn that this battle had a giant impact on the City, which I’ll discuss more below.

Five years later, aliens invade New York. I need to look at this closely to unpack why this is such an important moment in the MCU. When Loki goes to Berlin that isn’t an invasion, just a showy heist, and while the moment of him telling humanity to kneel is horrific, it’s also quickly thwarted by Cap, Widow, and Iron Man. The Chitauri invasion of New York is different: it’s protracted, broadcast on TV. An iconic building—this time Grand Central Station—is partially destroyed, and the film shows us Cap helping people out of the rubble and instructing the police on how to keep the crowd safe. So far, the parallels with 9/11/01 are obvious.

But the film also makes this a New York-centric event. This isn’t an Independence Day or Arrival type situation where the aliens showed up over the White House along with multiple other world capitals. In fact, the US government fires a nuke at New York, preferring to flatten the city in a bid to save the rest of the country. New Yorkers don’t even realize this is happening—there’s no warning, no time to say goodbye or try to flee. And that’s when the film goes in a fascinating direction that’s nearly a Jungian play on emotions. Tony learns about the nuke, intercepts it, and carries it up into the Chitauri’s wormhole. He tries to call Pepper, but first she’s so riveted to the news that she doesn’t see the call, and then his connection cuts out as he goes further into space. So we watch his phone ring and ring, with no answer.

And then Tony Stark, in front of millions of people, falls back to earth limp and apparently lifeless. This is the moment that shocked me when I saw the film in the theater. The call doesn’t go through. Tony and Pepper don’t get to say goodbye. Millions watch him die on television.

Again, the parallel with 9/11/01 should be obvious. But then the story turns. The Hulk catches his friend, and roars at him, which seemingly startles Tony back to life. The ending has been rewritten and New York has been saved, and as the credits roll we see the people who have been saved thanking the heroes, the beginnings of a superhero celebrity merchandising complex, and the way the media begins framing the heroes. We don’t see any bodies. We don’t hear that anyone died. The terrorist attack has been defeated. And here the film turns again with a tiny, seemingly flippant decision: Tony suggests they all go for shawarma. Not pizza or bagels or a buttered roll or a pastrami sandwich from the Carnegie Deli, but shawarma, a quintessentially Middle Eastern dish with an Arabic name. So having just created a new version of 9/11/01 with a different outcome, where the villains are an alien force rather than a human one, the heroes all celebrate with Middle Eastern food, affirming Arabic culture as another thread in the weave and warp of New York.

Processing the Aftermath on TV

While the films spun out across the universe after this point, the Marvel Netflix shows took us down onto the ground to deal with the aftermath of these “Incidents,” which is where we see something far more profound. The five seasons of Marvel shows on Netflix are probably the New Yorkiest of all the Marvel properties. (To start with, Matt Murdock and Wilson Fisk say the words “Hell’s Kitchen” more often than those two words have ever been said, by anyone, in human history.) Since these shows are “on the ground” they give us a non-superpowered view of life in New York in the Age of Marvels. Even more than that, though, they make constant meditative mention of The Battle for New York and The Battle of Harlem.

People search out the connections between the shows, the references, the photos of Stan Lee, but there is one thing that all the Netflix shows have in common. At some point in every single show, the heroes find themselves underground, threatened with a constant motif of collapsing buildings and scenes of heroes digging themselves out of rubble. In each series, they have returned over and over to scenes of rubble, destruction, bottomless pits, building’s foundations being dug up or compromised in some way. New York City is as much a character in these shows as Trish Walker or Foggy Nelson, and it’s New York City, over and over, that is hurt by the villains.

The entire first season of Daredevil jumps off from the idea that Hell’s Kitchen was particularly damaged during the Incident, and that it’s only just beginning to recover and rebuild. Thus the show becomes a discussion of Lower Manhattan in the early days of 2002, touching on the economic turmoil that came in the wake of massive destruction, and the lingering fear and trauma that affected people who were on the ground in New York during the attack. Wilson Fisk, rather than just being a drug-dealing thug, is now part of a larger network of people all trying to exploit the damage done to the city.

In the episodes “World on Fire” and “Condemned,” Fisk goes through with a plan to blow up buildings in Hell’s Kitchen as part of his overall scheme to rebuild New York in his own image. So…more urban destruction. But unlike the movies, we don’t experience this from the hero’s points of view. No, we’re with Foggy, Karen, and an elderly lady named Elena Cardenas when the building collapses around them. It’s their fear that we experience. Only after that, in the next episode, do we rejoin our hero Matt, and even then we have to deal with the reality of destruction far more than when we were watching Cap and Widow hop around in rubble. We go with Foggy, Karen, and Mrs. Cardenas to the ER, and we see a flood of injured people sitting in the hospital. No noble sacrifices or wormholes to fly into, here: just scared people, and pain, and nurses trying to help them. And underneath it all the terror of not knowing why buildings are blowing up.

Fisk the terrorist is using violence to foment fear, confusion, and division among people he doesn’t really see as people. When we check in with Matt Murdoch, he is tracking a Russian gang, and has, of course, found one of them in one of Fisk’s demolished warehouses. The two end up fighting each other while also fighting, together, to survive in a structure that’s collapsing around them. The episode cuts between the two as they work their way through the shambles of the building into the subbasement, and Foggy and Karen at the hospital, who are calling Matt increasingly sure that he’s under the rubble—which he is, but not in the way they think.

Karen and Foggy stand in for everyone who was left waiting during terrorist attacks, listening to a ringing phone and hanging in a liminal space between knowing and not knowing. It’s the human, mortal, non-billionaire/playboy/philanthropist version of Tony’s fall from the wormhole. Matt’s a hero, yes—he’s trained in martial arts, he has super senses—but he’s also still mortal, and this isn’t Jessica Jones with her super-strength or the nigh-indestructible Luke Cage. It’s a fascinating way to update the 9/11/01 motif for the grittier Netflix shows, because Matt is stronger than most of us, and we can live through him vicariously as he survives the falls and the crumbling concrete, but he is also under constant threat of death in a way that Cap and Tony never are. If Matt dies under a building, only his closest friends will mourn—no one’s going to watch him become a hero on TV.

Jessica Jones touches on the trauma of The Incident in two ways. First, in the episode “AKA 99 Friends,” Jessica is ambushed by Audrey Eastman, a woman whose mother died in The Incident. Audrey hates all super-powered people, and is trying to seek vengeance one person at a time. This moment is initially played almost for dark slapstick comedy, but then Audrey’s waving a very real, very loaded gun around, and sobbing about her mother, whom she will never get back. Jessica can tell her to “take it up with the Green Guy and the Flag Waver” but that doesn’t help anything. The deaths are real, the destruction is real, and most non-Stark (or Stark-funded) New Yorkers don’t have the resources to deal with their grief. Normal humans are still suffering because of the battle between Loki and the Avengers, all these years later.

Later on in the series we learn that Jessica and Reva Connors, Luke Cage’s wife, were forced to dig up a pen drive that showed Kilgrave’s parents experimenting on him—a pen drive that was hidden inside the foundation of an abandoned warehouse. Once again we follow one of our heroes into a crumbling derelict building, down into the rubble, and once again it leads to suffering as Kilgrave forces Jessica to murder Reva Connors immediately after this scene. The reason I’m focusing on this is simply that it doesn’t need to be here. Reva’s a psychologist, and Jessica Jones is a private investigator. They both work in offices, on computers (plus, as we learn in Luke Cage Reva’s also based in Georgia for much of her career), so why exactly is the pen drive buried under the foundation of a building in the West Side of Manhattan? Why not hide it literally anywhere else? But again, Marvel needs to use urban destruction as a visual shorthand for pain.

In the second season of Daredevil we return again to the foundations of a building, this time the mysterious warehouse on 9th Avenue that seems to be a cover for The Hand’s Mysterious Bottomless Pit that will presumably tie into a huge cosmic plot which will mean I have to listen to Stick drone on about weakness and strength for another goddamn season.

Sorry. I just…can we just drop Stick into the Mysterious Bottomless Pit? Please.

Finally, in Luke Cage, the other Incident is dealt with in a fascinating way.

But first, let’s back up a little.

When people talk about the MCU, they don’t often mention 2008’s The Incredible Hulk. (Edward Norton was a serviceable Bruce Banner; CGI Hulk looks a bit more CGI than the later version we see in The Avengers; things are smashed. There, you’ve seen the movie.) As I mentioned earlier, Mark Ruffalo’s Bruce Banner makes one deadpan joke, saying that last time he was in New York he “kind of broke… Harlem” which is funny until you put it in the context of the whole MCU.

What we have in that movie is a government experiment gone terribly wrong, co-opted by the military, which then crashes into the heart of Black America. (Any similarity to similar government experiments gone wrong is surely merely coincidental, right?) Two huge, terrifying monsters battle in Harlem, causing millions of dollars worth of damage to residential buildings, neighborhood shops, and the street itself, as well as to the historic Apollo Theater. And what we see, eight years later, is that the buildings are still a wreck, and people are still psychologically scarred. But no one talked about The Battle of Harlem in any of the other shows—we had Ben Urich’s front-page story framed on a wall, but that was it. This Battle is a footnote, the other Battle is The Incident. The US government broke Harlem, then walked away and left the residents to try to clean up the damage. Finally, eight years later, Marvel picks the thread back up to deal with the emotional fallout from the Other Incident, but you’ll notice that while people across the country were concerned with the Chitauri attack, Luke Cage makes it clear that the citizens of Harlem, largely people of color, are the ones doing the work in rebuilding that neighborhood, with little press or support.

What we have in that movie is a government experiment gone terribly wrong, co-opted by the military, which then crashes into the heart of Black America. (Any similarity to similar government experiments gone wrong is surely merely coincidental, right?) Two huge, terrifying monsters battle in Harlem, causing millions of dollars worth of damage to residential buildings, neighborhood shops, and the street itself, as well as to the historic Apollo Theater. And what we see, eight years later, is that the buildings are still a wreck, and people are still psychologically scarred. But no one talked about The Battle of Harlem in any of the other shows—we had Ben Urich’s front-page story framed on a wall, but that was it. This Battle is a footnote, the other Battle is The Incident. The US government broke Harlem, then walked away and left the residents to try to clean up the damage. Finally, eight years later, Marvel picks the thread back up to deal with the emotional fallout from the Other Incident, but you’ll notice that while people across the country were concerned with the Chitauri attack, Luke Cage makes it clear that the citizens of Harlem, largely people of color, are the ones doing the work in rebuilding that neighborhood, with little press or support.

When we look at Luke Cage’s personal arc across Jessica Jones and his own show, we return to the motif of the collapsing building. First he plants explosives in his bar, under orders from Kilgrave. He’s fine, physically, but now he has the wreckage of a building standing in as a big fat symbol for the failure of his attempt to build a new life. So he moves up to Harlem, and for a while seems to be finding a home in the heart of New York’s historic Black community. But wait: He lives in a small room above a Chinese restaurant called Genghis Connie’s.

Connie is his landlady, and is actually pretty nice about letting him pay in cash and occasionally run a little bit of a tab. But when he tangles with the local crimelord, Cottonmouth, things get ugly quickly, and Connie, longtime Harlem resident, true New Yorker, purveyor of Chinese food, is caught in the crossfire.

Once again a Marvel show decides on a very particular way to depict violence. Cottonmouth shows up on Luke’s corner with a freaking rocket launcher. Rather than trying to poison or drown Luke, Cottonmouth goes for the destruction of a building. And while this is obviously a great tactical show of force, it’s also the work of a terrorist, not a crime boss. And it leads to an extended sequence that plays again on Marvel’s particular obsession with the destruction of buildings.

Now here’s where I go out on another psychological limb. The episode “Step into the Arena” (IMO, the best episode of the series) sees Luke’s horrifying present cut together with his just-as-horrifying past. In the present, he’s trapped under the rubble of Genghis Connie’s, and while he’s fine, Connie herself is terribly injured. Luke begins to try to shift the concrete so they can escape. In the past, Luke is sent to prison for a crime he didn’t commit, and then forced into an illegal fighting ring. Luke is trapped in every possible way—physically he is beaten and abused, mentally he is subjugated and humiliated by the racist guards. It’s all just as horrifying as you’d expect. And these flashbacks to his origin story aren’t triggered, as they are in most superhero stories, by the decision to become a hero, but by being physically trapped beneath the collapsed building. This is what he thinks of, as he painstakingly shifts concrete blocks to create a path for Connie. Once again we’re under a building with a hero as concrete shifts and groans above us. It’s the weight of the city itself that threatens our lives.

The only saving grace here is Luke, falling with her. Luke, with his indestructible skin and super-strength, moves rock after rock, and digs both of them out. The two little guys, an underemployed black man and a Chinese restaurant owner, were supposed to pay for the illegal dealings of Justin Hammer—whose military-grade weapons have, of course, found their way to street-level—but instead they live. Just like all the commuters saved by Cap in The Avengers, the ordinary New Yorker survives because a super-powered New Yorker is there to shield them from a falling building.

Luke goes back the next day, and in sifting through the wreckage of his apartment he finds the swear jar that used to hold pride of place in his friend Pop’s barber shop. He’s able to easily pick up rocks and bits of wood, no fear of the shifting beneath him because even if it all caves in and takes him with it, he can just brush it off. He’s able to rescue the tiny piece of Pop’s life, put it back in the barbershop where it belongs. After all the trauma, he’s able to move on again.

Cosmic Terrorism

I’m focusing on New York, for obvious reasons, but throughout Captain America’s Trilogy and Avengers: Age of Ultron, terrorism = the mass destruction of cities, including Lagos, Johannesburg, and Sokovia. Even when Marvel goes cosmic it uses the language of collapsing buildings and cities under siege to make its emotional points. Ostensibly Guardians of the Galaxy and Doctor Strange are supposed to take us to new realms, outer space, alternate dimensions—so why in both films does the final battle take place in a city? GotG could have had any plot, but the writers chose to make the antagonist a second-generation terrorist, and while Ronan falls prey to the usual “underdeveloped Marvel villain” syndrome (despite Lee Pace’s best efforts) his few flashes of spark come down to this: he wants to destroy a vibrant culture because it offends his own fringe religious beliefs. He’s a fundamentalist Kree who wants to destroy the pointedly diverse, inclusive culture of Xandar, and he’s doing it against the wishes of his own culture. This is the story of every terrorist raised in a hateful belief system, from KKK members to Taliban suicide bombers to ISIS kidnappers. Of all the stories they could have told, Marvel chose to bring the cosmic down to the human level by showing us a madman attacking a city as civilians fled. What is this but yet another retelling of 9/11/01? An attack on the ideals of inclusiveness and freedom of choice that are at the heart of the American experiment, the ideal we’re all supposed to be working towards? And in Doctor Strange, a story where people could literally fight as astral projections, the big ending battle still comes down to a city filled with vulnerable, non-super-powered humans, who, fortunately, have a few super-normal people protecting them.

Obviously we’re in Hong Kong, not New York, but Marvel still wants to be sure we understand the true cost of superheroes and villains duking it out, and to do that they keep returning to the visual language of terrorist attacks. When Strange’s twisting of time finally reveals Wong’s fate, we learn that he wasn’t killed by Kaesilus himself, of even one of the mystical minions: he was crushed under rubble and impaled on rebar. Not stabbed by a magical weapon or felled by a spell, but instead killed in a building collapse like a regular human. And then Strange turns time again, the chunk of concrete flies back up, the rebar extracts itself, and Wong is alive again. Doctor Strange uses the Eye of Agammotto to literally turn time back, to undo the attack, bring the people back to life, rebuild the Sanctum. We watch the building in reverse flying back up into the sky, bricks joining, city healing.

Writing a New Ending: Save the Villain

In Spider-Man: Homecoming we get a new rewrite of terror. We meet the children who grew up in the shadow of the Incident—and it soon becomes clear that in this version of the Spider-Man mythos, the most New York of all Marvel’s heroes will try to give us a new ending to a terrorist attack.

The movie begins in the rubble of The Avengers. Adrian Toomes, the head of a salvage crew is cleaning up the mess the Chitauri left behind…until a Stark company comes in and screws him out of the contract. Here, finally, is the villain Marvel has always needed. Just as Marvel’s heroes are complicated, even morally grey at times, Toomes makes some extremely good points during his villain monologue. He did get screwed over by Tony Stark. He wouldn’t have turned to a life of crime if his business had been respected. He is just trying to give his family a good life. He is a class war personified: the blue collar construction guy now has a huge house and pool in the suburbs, a nice car, a loving wife who can afford stylish clothing (we never learn if she works) and a daughter who can be the pretty, well-dressed, popular queen bee of a nerd high school. He’s paid for this life with his crime, and if he tries to stop now, it all collapses—no more upper middle class. What does that do to his daughter’s college prospects? What does it do to his stable marriage? What does it do to his pride as a provider?

Here are stakes that reflect our world as it is now, and here, as in the Defenders, the sort of conflict that force otherwise good people to treat terrorism as a solution to their problems.

On the other side is Peter, living with his newly widowed aunt, and trying to make life as a hero work, and the New Yorker all of us want to be: friendly, resourceful, snarky, heroic, but down-to-earth enough to argue about bodega sandwiches with Miles Morales’ uncle. (!!!! DO IT, Marvel. Don’t just hint at Miles and then not give him to us.)

(But also please don’t kill Peter off to do it.)

Anyway. Of course he jumps in to foil the arms deal on the Staten Island Ferry, and of course he fails—unlike the previous Spideys he’s truly just a kid. The Ferry, The Spirit of America no less, is not the big iconic THIS IS NEW YORK moment, however. As I hoped when I saw the first trailer, it’s only the halfway mark. Here is this iteration of Spider-Man’s take on that iconic subway fight: once again, the kid from Queens attempts to save New York’s commuters while posing in as cruciform a manner as possible. But here, crucially, he screws up. His interference in the Staten Island Ferry situation nearly kills a lot of people, and pisses Tony off so much that his suit is revoked, he’s publicly humiliated, he loses any hope of joining the Avengers, and is finally sent home to his terrified aunt.

For a few scenes, the film is all about Peter learning to be a normal teen again, devoting himself to friends, family, and school, and trying to apologize and be there for the people he let down. The film could have continued in this vein, with Peter learning the importance of being a friendly neighborhood Spider-Man by seeing how much good he does in small ways. Instead, the film turns and becomes a commentary on New York’s unique relationship to terrorism. Peter learns that Toomes and his henchman plan to hijack a Stark plane and steal Chitauri tech to create more weapons of mass destruction. Since the grown-ups refuse to listen to his warnings, Peter has to be the hero again.

He confronts Toomes in a giant warehouse, and the man intentionally monologues in order to trick Peter into letting his guard down—Peter having been trained by all superhero narratives that once a villain starts monologuing, you’ve all but won.

Then Toomes demolishes the supports beams and brings the roof down.

We’re with Peter—say it with me now—TRAPPED UNDER A BUILDING. And for a good five minutes something happens that I don’t think has happened in a Marvel movie before—all heroics are dropped, and for a little while Peter is just a terrified crying kid. Because, far more than Tobey Maguire or Andrew Garfield, this Peter Parker is a kid. He forgets he has powers. He doesn’t have Cap or Luke Cage under the rubble with him to help. He isn’t engaging in some giant moral dialogue like Daredevil, or undoing time like Strange—he’s just scared. Alone. And then he sees his reflection in a puddle, wearing his old, homemade Spider-Man mask, and he rallies:

“Come on Spider-Man. Come on, Spider-Man.”

Peter Parker, kid from Queens, can’t move the rubble. But Spider-Man is New York’s hero. He rescues bodega cats. He risks his skin to hold the ferry together. He can’t allow Vulture to hurt the city again, and without Iron Man or Cap around to be the hero, it falls to him. The first time I saw this film it was in a packed theater in Brooklyn, and I heard plenty of people around me crying. What does it mean to a New Yorker who maybe teared up watching those New Yorkers pelt Green Goblin with rocks in the first Spider-Man all those years ago, to now see Spidey stand up and shake rubble away? What does it mean to see him emerge from that building?

He goes after Toomes, and the next few scenes are Spider-Man fighting a villain on a hijacked plane as it flies low over New York City landmarks. He uses his webbing and sheer strength to steer the plane over Brooklyn, barely misses a residential building, and crashes the plane into Coney Island’s beach. The only landmark harmed is the Parachute Jump, and the borough’s citizens are safe, but now Peter is at the mercy of Toomes.

This is Peter in his old suit, with no snazzy Stark Tech cushioning, no taser webs, against a tough adult man in a metal flying suit, but Toomes doesn’t hold back. Their fight soon turns into a beating, with more the brutality of a fistfight between Cap and Bucky than any of Spidey’s previous cinematic battles. Toomes only stops short of killing Peter right there on the beach because he sees a box of Chitauri artifacts and decides to escape with them.

But then the story turns again. Toomes’ wings short out. And in contrast to all the previous Spider-Man films where Peter is lectured on morality, and tortured over doing the right thing, Tom Holland’s Peter calls out a warning with no hesitation or moral quandary.

Toomes ignores him and the whole rig explodes in a fireball. Watching the film the first time, I thought we were going to go down one of two paths: either a cut to black, followed by Peter waking up on the beach and The Vulture escaped to wreak havoc another day, or The Vulture dead, with a morally-conflicted Peter free of the man who threatened him with a gun, swore to murder everyone he cares about, and brutally beat him, but also scarred by his experience. Either ending would set the film up for a sequel, and leave Peter darker and older than he was at the start of the adventure. But the movie rejects both of those possibilities to, once again, rewrite the ending to a tragedy. Peter drags himself up off the sand and walks into the fire to rescue the villain. After all the horror Toomes has wrought, he’s still a person, and Spider-Man is obligated to save his life. Rather than dying in the wreckage of a hijacked plane, both men get another chance at life.

Writing a New Ending: The Heroic Terrorist

The Defenders gives us the apotheosis of this drama. When a series of tremors rock New York City in the opening episodes, the idea that it’s an earthquake is quickly dismissed by most people. When New Yorkers call into Trish Talk, they ask if it’s another Incident or earth-grown terrorism, but when she tries to investigate she soon finds higher-ups heading her off. The T-word pops up almost as often as the H-word over the first seven episodes. And then, of course, we have the culmination of Marvel’s obsession with urban destruction: the heroes become terrorists. Colleen Wing suggests that blowing up the Hand’s headquarters might finally stop their horrible plans for New York, and the rest of the Defenders reluctantly agree. True, they have a very good reason, but once again purest evil is described in terms of explosions, falling buildings, and free-form chaos. Once again the narrative lands us in a pit, with the foundations of a giant building collapsing into dust around us.

And of course this is complicated by Daredevil. Matt hangs back, tells his friends to go ahead and escape, and succumbs to the siren call of Elektra. Because at the core of Matt’s moral struggles, and his open desire to “save” Elektra, there is also his desperate, self-destructive love for her. You could argue that he didn’t want to abandon her, or that he thought he might shield her body, or even that he could convert her in the last moments, but the grin on his face as the building collapsed did not suggest a man meditating upon spiritual matters…which, I would argue, is what keeps Daredevil interesting. But to go a step further, Matt has fulfilled the destiny started with those unanswered phone calls two series ago, as we see when Foggy and Karen gradually realize he hasn’t made it back alive. The MCU has now given New York its own religious martyr to balance out the religious martyrs who attacked the city on 9/11/01.

We later learn that Matt’s final words to Danny Rand were “Protect my city.” New York, battered and nearly destroyed by terrorism, has now been saved by it, one of its homegrown heroes has sacrificed himself for it, and his mission has passed to a new hero, whose arc reaches its own climax a few scenes later, when he admits that New York is starting to feel like home. Cheesy, yes, but it was enough to make me (grudgingly) like Danny Rand.

The MCU has been defined by terrorism since its inception. And while it made sense for Tony Stark, war profiteer, to reckon with the consequences of his career as a weapons manufacturer, over the past decade Marvel has come back to this primal, man-made horror over and over again, forcing its audiences to relive the attacks at the turn of the century. Buildings fall over and over again, we watch rubble and explosions, we see people pinned under foundation beams and crawling out of broken concrete. Even in a universe where Norse Gods wrestle Hulks, the gravity of a situation is measured by how it affects a city’s infrastructure, nearly always New York—because attacks on New York are personal to Marvel. But in Marvel’s universe there are heroes to turn time and put the buildings right again. The hero can rise above all the anger and hatred to rescue the terrorist, meeting hatred with love. And if even that doesn’t work? The heroes will take terrorism into their own hands to ensure New York’s safety.

Marvel keeps processing this tragedy, replaying the attacks and finding new ways to save their city. Each time you can see them tilting the narrative, looking at tragedy from new angles. For the MCU and its Netflix progeny, terrorism is a puzzle to be solved. If they keep repeating the collapse and the terror, they seem to say, someday they’ll find a hero who will defeat it.

Leah Schnelbach likes the newest Spider-Man’s method the best. You can come discuss rubble with her on Twitter!

Lesson learned – don’t live in NYC. Just like if you’re a Whovian, you don’t want to live in London because every alien invasion ever begins there.

Interesting analysis, thank you. But I still don’t agree with some points, or rather, I think you’ve stretched things to fit your narrative that weren’t intended as you interpret them, like Cottonmouth using a rocket launcher to kill Luke instead of poison or drowning. The answer is quite easy, it doesn’t have anything to do with terrorism imagery or destroying New York buildings: it’s obvious they’re not going to kill Luke, so they’ll use this assasination attempt as a way to show just how invulnerable he is.

And in any case, buildings crumbling during superhero fights are part and parcel of superhero fights since long before 9/11. But yes, New York is another character in Marvel Comics.

On another note, why is it dumb that the train in Spider-Man 2 is elevated, when there are plenty of elevated trains in New York City? Even moreso in Queens (though I don’t remember what part of the city that fight with Doc Ock was in).

Damaged building collapse, that’s what they do, and there are lots of builldings in NYC. Plus, destroying forests, corn fields, pig farms, and suburbia just isn’t visually fun.

Good article. Thanks!

Thanks for this, was a great read while stuck at work.

Super-tiny quibble: Loki goes to Stuttgart, not Berlin, in The Avengers.

As a lifelong New Yorker, I appreciate this article even if I don’t agree with all of its points. The central point about the importance of New York’s presence in the MCU, specifically the Netflix series, (and New York itself being a central figure) I am totally behind and supportive of- even if none of the actors/actresses are real New Yorkers (but at least Scott Glenn, who plays stick, lives in NY- so does the original Professor X, Patrick Stewart, even if he’s British).

MaGnUs: There are plenty of elevated trains in the outer boroughs, but almost none in Manhattan, which is where that scene in Spider-Man 2 took place. The Metro North commuter rail goes above ground from 96th Street to 125th Street over Park Avenue, and the 1 train is elevated from Dyckman Street to the top of Manhattan over 10th Avenue (and also briefly at 125th Street over Broadway), but that’s it.

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

That was why I asked, I didn’t remember what part of the city the fight was in. That might have been useful to include in the article line saying it was dumb.

During the events of 9/11, I was playing in a long-term Champions superhero RPG which had a group of characters set in NYC; the timeframe was a bit different, in-game it was a few years before the towers fell. When we caught up to 2001, we decided the event had to happen, it was too powerful an event to skip out, and actually played into the themes of the campaign quite well (“do those with the power to change the world have the right or responsibility to do it” was a major theme, as was the arms race of super powered beings vs. “normals”, so a world-changing event triggered by “normals” had a massive impact).

The main line was played through email, so the GM had us write up what our characters did during the event. We all did it individually, but all of us came up with a story about helping the people. We weren’t so super powered that we could have changed the event; the most powerful of us was about Luke Cage/Jessica Jones level, so rescuing people during & after was what we could do. It was an interesting experiment, and was a sobering look back on one of the worst days in NYC history. One of the players was actively living in NYC at the time, so it touched him deeply.

A fascinating piece thank you.

Just one quible about the section on Tony Stark.

The Ten Rings is a legit organisation of Terrorists in MCU, with parallels to the Taliban or ISIS as a global terrorist group. The group that sieze Tony are not hired muscle, they are the local warlord/ cell of the Ten rings who are paid in munitions to target Tony.

The Mandarin we meet is not the real Mandarin, nor the leader of the 10 rings (who is a shadowy figure) but is merely a character invented by AIM in order to cover up their actions. The real Mandarin is upset by this and instigates the break out of the fake Mandarin in a MArvel one shot “All Hail the King”.

It is a small quibble really, but is actually closer to the metaphor of terrorism in the MCU than you describe.

Its a very interesting article, and I enjoyed reading it. But I’m not sure the symbolism of urban terrorism is a direct response to 9/11. After all, so many superhero movies prior to 9/11 also dealt with this issue. Superman 2 and Batman, in particular, both involved protracted fights in cities where buildings were being destroyed. And Superman even had the visual of having to pick himself up out of the rubble.

@1:

At the very least, don’t be in London at Christmas.

Anthony, like I said before, urban property destruction is standard fare in superhero fiction. Even if you accept the premise that the Marvel Universe has stronger ties to a post 9/11 anti-terrorism metaphor, because New York City is central to it and not fictitious cities (even if Gotham and Metropolis are stand-ins for aspects of NYC)… Marvel Comics stories have featured urban property destruction since long before 9/11.

Movies and TV shows just ramp it up to 11 because it makes for a good visual spectacle, and it even subtitutes for some of the more fanciful things (not in terms of special effects but in stretching suspension of disbelief) that the majority of viewers (non-comic readers) might find harder to digest. Luckily, comic book movies are more like actual comics as time goes on.

After reading this article, I have come to the conclusion that the media and many moviegoers are really hypocritical. They didn’t pitch a fit over the destruction featured in movies like “The Avengers” and “The Avengers: Age of Ultron”. But when the Kryptonians under General Zod nearly destroyed downtown Metropolis with their World Machine in “Man of Steel”, both the media and many moviegoers got into a snit fit over the destruction, accusing Zack Snyder and the film’s writers of going too far. I’m not only amazed at this hypocrisy, but also disgusted.